This is the third entry in our series on the use of AI techniques in the three contexts explored in Patterns in Practice (see our previous blogs on education and drug discovery). The post is one of two, focused on arts practice. In the first, we provide a brief overview of the history of AI in arts practice and discuss key critical and ethical questions such as authorship and originality of AI artworks and the value of creativity in art. Part two focuses on how artists use AI as a topic within an art work. Through example artworks, we begin to consider critical perspectives including limitations and discrimination in AI.

The rise of AI-assisted creativity in the last decade

The explosive growth of data generated in everyday life, including education and science, new data mining techniques and the development of computationally intensive methods such as machine learning (ML) have led to the rise of AI-assisted creativity in the last decade. The Alan Turing Institute suggests that these developments have affected the arts sector in two ways. On the one hand, artists use AI as a tool aimed at generating aesthetic outcomes. On the other hand, artistswork to better understand, analyse and critique these developments and technologies, treating AI as a topic within the art work. Audiences can therefore meaningfully engage with or experience AI for themselves.

AI as collaborator: debates on authorship and originality

Neural Style Transfer (NST) is one of the ML techniques used in arts practice. It was developed in 2015 by ML researchers Leon Gatys and colleagues. NST consists of a family of algorithms that manipulate digital art pieces to replicate, imitate, and combine different styles of artwork. It can be applied to paintings, photographs, videos and musical compositions. A well-known example of the application of Neural Style Transfer is Google’s computer vision program DeepDream created by scientist and artist Alexander Mordvintsev. DeepDream uses neural networks to find patterns in images and create dream-like and deliberately overprocessed images.

Critics of NST’s algorithms argue that artists and audiences quickly got bored of this type of art. It is also suggested that these algorithms are essentially just “a fancy Instagram filter” as no new computer programmes and detailed codes need to be written in order to use them. This links back to the criticism of cyber and digital art, according to which the creative input of artists using this technology is minimal.

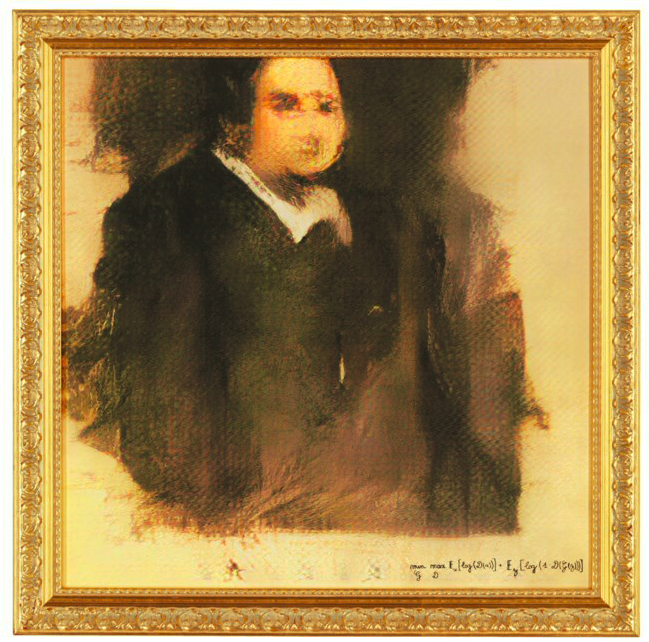

Another trend in machine learning–based art is the use of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) introduced by Ian Goodfellow in 2014. GANs art requires more programming knowledge than the NST and DeepDream interface and is now a frequent tool used by artists. Artists using this technique set up algorithms to ‘learn’ aesthetics by analysing a number of random images to generate new images that follow this aesthetic. In this process, the artist supervises the training data and can therefore control the outcome to some extent.

In 2018, exceeding all public expectations, the artwork generated using GANs entitled Portrait of Edmond Belamy was the first AI work sold for $432,500 by Christie’s auction house. The piece was created by a Paris-based art collective called Obvious and attracted a lot of interest from the arts community. It also raised ethical questions about the originality and attribution of this artwork. The portrait was criticised by the AI-art community “for being derivative and not original ”. It was alleged that the code and dataset used to create the artwork was not written by the authors. After the criticism, the Obvious collective admitted that they had used code written by another AI artist, Robbie Barrat, and had only slightly modified it.

This criticism directed at AI artwork has raised some important questions strongly related to art practitioners’ values but also beliefs, such as: what is AI art? And whether art can be generated by a computer? In response, Elgammal, founder and director of the Art and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at Rutgers, suggests that AI art is conceptual art and looking at it as a process, rather than just an outcome, can resolve the issues of attribution and originality. Referring to Edmond Belamy’s Portrait, Elgammal asks: “if you take the code and the same input dataset and press the button to repeat the process, can you claim the outcome is your art?”

Data mining and ML – or ‘narrow AI’– is not only used by visual artists. Sound artists, poets and writers have also integrated the use of these technologies into their practice. Vicky Clarke, for example, is a sound and electronic media artist from England. For the last two years Clarke has been artist in residence at NOVARS and is interested in how we relate to technology for exploring sounds. Clarke is exploring whether ML could be a modern tool for musique concrete and the role that the artist plays when generating sound with ML. Clarke states that she is particularly interested in understanding the role of autonomy and creativity in the process of making music with ML and the decision making involved in it (e.g. What are the decisions made by the artist and in which ways do humans collaborate with the machine?).

Pharmako-AI, one of the first books co-created with machine learning, reflects on a similar point. The book collects essays, stories, and poems and is co-created by writer K. Allado-McDowell. The writer used OpenAI’s GPT3 language model, a neural net that generates text, to work on the book. OpenAI’s chatbot attracted recent media attention, with practitioners and policymakers speculating on its creative uses, but also the copyright challenge introduced where the originality of the work is crucial, such as within higher education and student essays.

AI as a creator: can human creativity be surpassed by machine creativity?

To transform GANs to make them creative, in 2019 Ahmed Elgammal created AI Creative Adversarial Network (AICAN). AICAN is described by Elgammal as a ‘nearly autonomous artist’ that has learned different styles and aesthetics and can create innovative visuals on its own (Elgammal, 2018a). Trained by 80 000 images that represent the Western art canon over the past five centuries, AICAN creates images choosing the style, subject, composition, colour, and texture. However, AICAN is not able to tell stories and make sense of the world. Despite this, when it comes to the values shared by art practitioners, evidence that many find AICAN’s work financially valuable is that one of AICAN’s pieces recently sold for 16, 000 USD at a benefit auction in New York (Elgammal, 2018c). This fact is foregrounding the Western art canon, rather than diversifying it.

The emergence of AI-Da in February 2019, the world’s first ultra-realistic humanoid robot artist that can draw, paint and sculpt ‘using cameras in her eyes, her AI algorithms and her robotic arm’, has also raised important questions about the nature and meaning of art and the role of creativity in society now and in the future. The robot artist had many exhibitions including a solo show during the Venice Biennale at the Concilio Europeo Dell’Artw in the Giardini in 2022.

On the one hand, it has been suggested by some art practitioners, researchers and academics that human creativity could be surpassed by machine creativity. On the other hand, some authors argue that artworks produced by machines pose no threat to human artists. For the latter, AI is seen as an opportunity to challenge human creative boundaries, and human-machine collaboration can lead to exciting new creations, new ways of working for artists, and new art experiences for audiences. In other words, AI can support artists in developing creativity by creating art that challenges existing notions of the art, artist and creativity in a post-humanist era.

Such applications of ML technology to art raises important criticisms about the commercial marriage of art, technology and aesthetics and the implications of this for society. It is important to consider who is commissioning AI-driven arts projects, for what purpose, and who benefits. It is also a question of what values, financial, or otherwise, that these people hold.

Patterns in Practice and AI in arts sector

The examples given in this blog post show that the growing use of data mining and AI-based technologies in the arts sector has raised some critical and ethical questions. Artists, art workers, academics and researchers have been discussing issues such as authorship and originality of AI artworks, and the nature of creativity in art. Our research seeks to explore how different art practitioners’ beliefs, values and feelings interact to shape how they engage with ‘narrow AI’ and data. The artistic context is uniquely suited to these considerations in our study, as, in addition to producing ML effects that can be experienced (and manipulated), it can also offer a critique of AI and the implications of these wider cultural dynamics of ML and data for society. This later point is considered in our second post: AI art as a topic (to be published soon).

Authors: Monika Fratczak, Itzelle Medina Perea, Erinma Ochu